Bronze. The word itself has musical resonance, like the ringing of a

bell. An alloy of copper and tin, this fabled metal has been prized

through the centuries for its strength and beauty. Many of the great

treasures of human culture have been shaped in this warm and enduring

material. In the popular imagination, bronze has been unfairly relegated

to a distant third place behind gold and silver (one thinks of

Olympic medals) but its debased status is undeserved. Gold shines radiant

as the Sun, silver glows pale as the Moon, but bronze is like

the Earth: solid, attainable, satisfying to the touch. As a dealer in

fine antiquities, I have long appreciated the versatile beauties of

bronze. Whether on the heroic scale of monumental sculpture or on the

intimate level of a Roman coin, bronze conveys an unmatched impression

of richness and strength.

Since the Renaissance, discerning connoisseurs have vied with each

other to collect the finest antique bronzes. The demand has been

steady, but the prices for such treasures have remained remarkably

stable. In a time when even a modest Impressionist painting is out of

reach for the average collector, superb and important bronzes can

still be had for reasonable sums. When acquiring any work of art,

personal tastes should take precedence over economics, but ancient

bronzes make a timeless appeal to the senses that will never go out of

fashion. As with all antiquities, prices will continue to climb as

the available supply narrows, but masterpieces can still be found.

What sets bronze apart from other metals is its patina. The surface

of gold remains indifferent to the passage of time, silver tarnishes,

iron rusts, but bronze acquires character and distinction. The patina

of an ancient bronze is an indelible part of its appeal. To remove it

would be like adding plaster arms to the Venus de Milo: a violation of

its artistic integrity. Not all bronzes are patinated, but connoisseurs

agree that a fine patina adds enormously to an object’s worth

and beauty.

A word about the survival of bronze artifacts. Perhaps more than any

other type of antiquity, bronzes owe their survival to the whims of

fate. Metal has always been a prized commodity, and few cultures have

had qualms about melting down the bronze heritage of previous generations

for their own use. The most famous ancient bronze, the Colossus

of Rhodes, was broken up and sold for scrap in A.D. 635. 900 camels

were needed to cart away the metal. Many other bronze sculptures met

a similar fate. The physical destruction of Ancient Rome was due more

to the city’s Medieval inhabitants searching for metal than to the

sackings of Barbarian hordes. As a result of centuries of recycling,

large-scale ancient bronzes are extremely rare, and smaller objects

have only escaped destruction by being buried or overlooked.

In A.D. 135, when the followers of Shimon Bar Kokhba made their last

stand in the Qu’mran Caves against the Roman legions, they carried

numerous bronze objects into hiding with them. The intrinsic value of

such booty made it worthy of being saved even in a desperate hour.

After the rebels’ defeat, many of these artifacts lay forgotten in the

caves until modern times. Several of the bronzes in my collection

were found near Qu’mran, very possibly the legacy of that ill-fated

revolt. These include an incense shovel which probably did service in

a Judaean synagogue, and an elegant bronze inkwell, stylistically

dated to the period when the Dead Sea Scrolls were written in Qu’mran.

Perhaps the scribes of those precious documents dipped their pens into

this very vessel.

Bronzes offer a superb record of the dialogue between men and their

gods. For thousands of years, bronze votives were considered the

ultimate offering to the heavens: costly, enduring, certain to gain

benevolent favor. Left by unknown men and women for gods now equally

forgotten, these votives can be quite touching in their implications.

They represent human hopes and dreams, wishes for health, wealth and

happiness which have altered little through the course of civilization.

Such a gift might guarantee a successful harvest, victory in

battle, or cure from disease. As we hold some small token in our

hands today, we think of the person who left it long ago and wonder if

their prayers were answered.

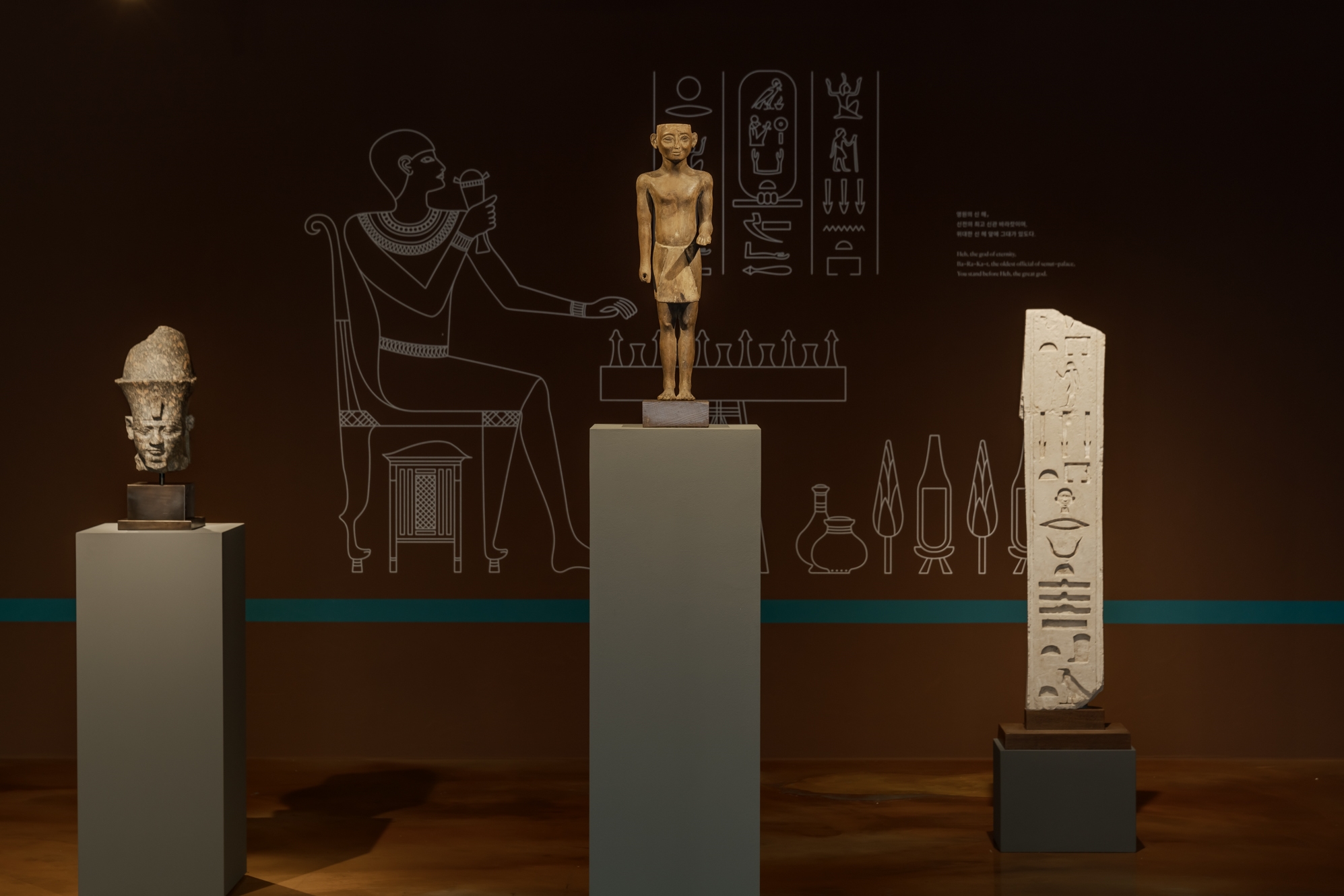

Bronzes bring us face to face with the gods themselves. The Egyptian

Sekhmet, lion-headed goddess of war and sickness, is supported by an

obelisk inscribed with the name of the votary. Regal and mysterious,

she remains today as the only clue to that ancient life. Ptah, patron

of craftsman, possesses a somber but benevolent dignity; twenty-five

centuries ago he was perhaps offered by the very artist who shaped

him, in thanks for the gift of talent. A graceful Greek statuette depicts

Apollo, god of learning and the arts. Nude save for a laurel

crown on his head, he is the ancient ideal of masculine beauty.

Though not large, this Apollo has the commanding aura of sculpture on

a much larger scale. He may be copied from a masterwork by Lysippus

or Praxiteles. Elegant, divinely self-assured, he evokes the very

soul of the Classical world.

A Late Roman bronze shows Hygeia, goddess of health. She too seems to

echo a larger prototype, possibly the cult image from the hospital

sanctuary at Kos. As befits a healer, she appears calm, serene and

benevolent. In her left hand she holds a serpent, one of the two that

twines around the physician’s caduceus. In the twilight of the Classical

age, she may have stood guard over a doctor’s practice. Even in

the modern world, where medical miracles are commonplace, it couldn’t

hurt to have Hygeia’s blessings.

Time plays tricks. Though the vast majority of ancient bronzes served

a practical function, in the modern world we accord them the status of

art, as if they were shaped solely for aesthetic pleasure. As we admire

the graceful, flowing lines of a bronze Etruscan pitcher, it is

easy to forget it was created to hold wine at table. Weapons-daggers,

axe heads, spear points– lose their sinister demeanor, and

assume an abstract purity of form. Though they may remember the heat

of distant battles, it is their sculptural elegance that appeals to us

today. Coins passed hand to hand at the height of the Roman Empire

bear the portraits of proud Emperors. Richly patinated by the passage

of centuries, such tokens evoke the grandeur of a vanished world. It

is as if those ambitious men understood that bronze would affirm their

rank and importance long after they themselves had disappeared.

Empires, after all, may rise and fall , but the solid beauty of bronze

endures.

To see a small sampling of ancient bronze masterworks from the collection please browse through the selections below.